Game Design Gone Engineless

So, this summer I've been focusing on my habits, and biggest of all, the game design-shaped hole in my cold, stone heart. This was initially prompted by LogLog Games' post on Rust gamedev, which was a post that helped me understand the difference between people who make games and bumbling idiots with too much time on their hands (and the affirmation that I fit square in the latter group).

I had decided that my summer project was going to treat the web as a first-class citizen, and taking my first step into the former category, I chose Godot as my engine. Right now, the situation for Godot 4 on the web is... complicated. C# is completely unsupported, and GDExtension has complicated support requirements on the web (but will quickly mature with WASI stabilization). Godot 3 fares better, with C# support, but GDNative is unsupported, and I wanted a chance to try godot-rust, despite the wasm32-unknown-emscripten target being weird and restricting the ecosystem of web targets.

Hello, Rust User from The Future™! By the time you read this, you might not even have a

wasm32-unknown-emscriptentarget. Work is currently being done to stabilize the C ABI for wasm32 targets, projected by September 2024, so this isn't even something you'd have to think about. Classic past frostu8 with his past-world problems.

Of course, the next logical step was to wipe my computer and make a game in pure Rust. Learning is overrated, and my dreams can barely fit in my pants, let alone my head.

For context, my game (working title soda) is a board game. This is distinctly not a real-time game, and instead only updates based on user interaction. Passage of time is completely irrelevant to the game logic, and because the networking is built with this expectation, it'd be very difficult to actually involve the passage of time.

No Engine!

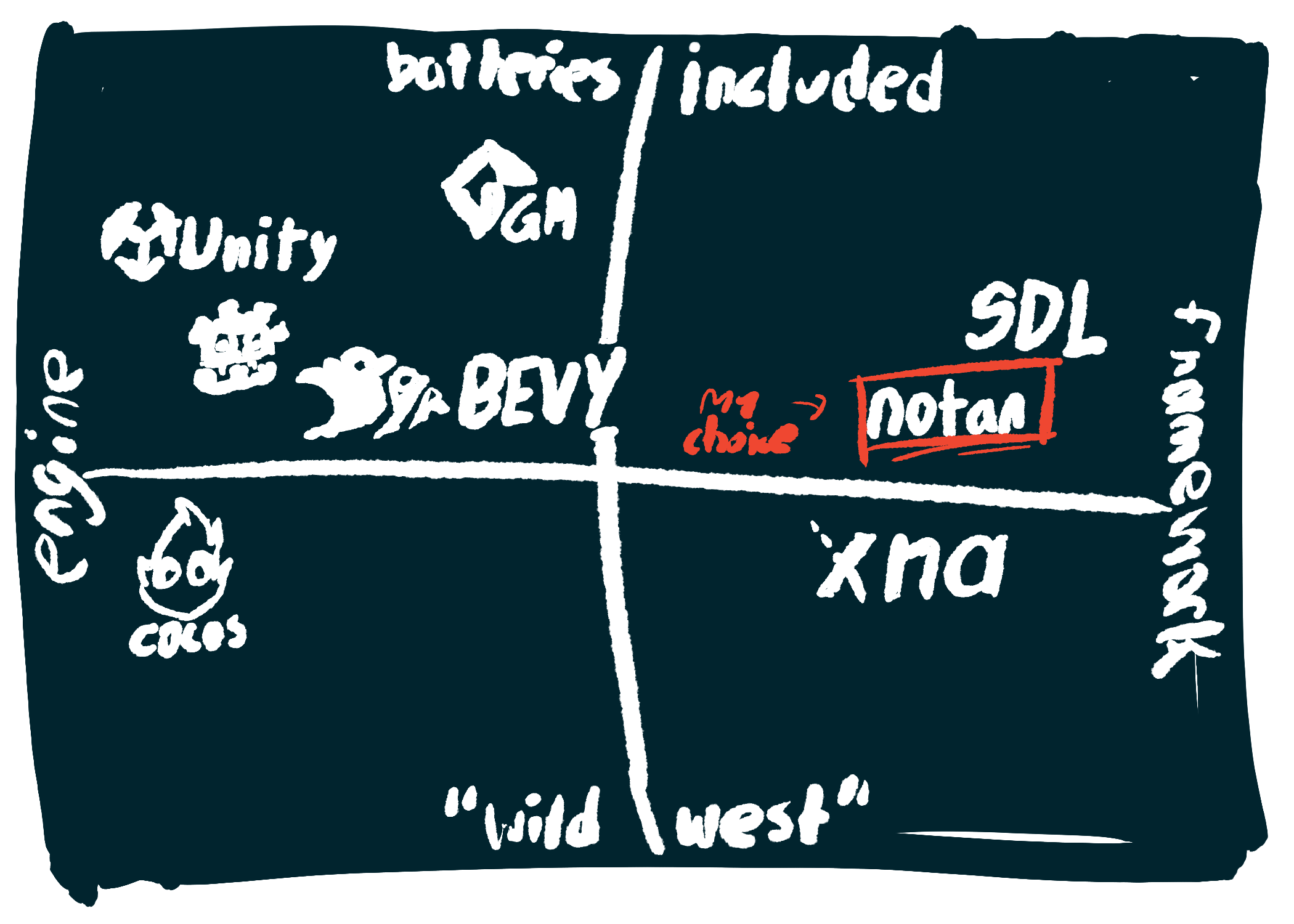

I feel a lot of developers seem to misconstrue the implications of having no engine. First, let's make something clear: I'm making a game with no engine; frameworks are still allowed. The definitions get mixed sometimes understandably, so I'll define them as rigidly as possible below.

We can probably argue about the proper placement of these things for a while. Whether or not using a multimedia framework for a game is considered "using a game engine" is left as an exercise to the reader.

| Engines | Frameworks |

|---|---|

| Control over game loop is left to the engine. | Developer still has high or total control over system execution. |

| Developer encouraged to use provided representations of data. | Developer pulls whatever they want to represent their data with rigidly defined inputs and outputs. |

| Optimized for game production, like with GDScript. | Optimized for abstract usage, for games, apps, tools, etc. |

For my game, I chose notan, because its design goals align with mine (web as first-class citizen) and uses wasm-bindgen so I can actually use wasm-bindgen tooling and pull crates like wasm-bindgen-futures instead of ripping my hair out with macroquad and maintaining an extra JS codebase.

This is great, because whenever I have a problem that needs solving, I can just pull another dependency to solve the problem! arewegameyet.rs is a center of people that have already solved problems in much smarter ways than you could ever conceive, and if you don't like the way one library did it, you can just find another one. Take the ~14 scripting languages available on the site as an example; there's bound to be at least one language that fits your use cases.

But this pro is often overstated, as game engines already have this figured out. Most of the time, your game engine already has included implementations to solve any problem you might have, tailored specifically for game development, and opinionated for the engine to boot! This is a huge boon to have. In a game engine, if the provided facilities don't solve your problem, it's typically a sign that you need to re-evaluate your approach.

"Typically" a sign. There are plenty of problems that require custom implementations to solve.

By using a framework, you discard all of these implementations for more control, which isn't necessarily bad, but most projects don't need this extra control.

In my opinion, the most powerful pattern in game design is the observer pattern, and flavors of it are in every game engine I know, generalized for developer use:

When C# was designed, the designers decided it was so important to have this that they literally baked it directly into the language. This isn't a joke, and by extension any game engine that allows C# for scripting (Godot, Unity) gets these superpowers for free.

For the case of my game, I spent a lot of time thinking about how to push events around. Thankfully, I would have to reimplement my own flavor of events anyways for the scripting interface, but there were other details like how to render and animate the game view I had to work out when I could have been making a game.

Easy to maintain code...

...if you know your design patterns.

There's something refreshing about seeing a classic game/event loop. Nothing gets me going quite like it.

fn main() {

let mut state = State::new();

loop {

let event = get_event();

state.process_event(&event);

state.render_game();

}

}

This is Tetris with all the fat trimmed off.

Having complete control over what gets executed first, and then after that, and then after that is great. No more 1-frame lag problems because the entire game update logic is all splayed out in one big line-of-execution, ready to dissect.

This great power comes with great responsibility, though. If you're not careful about your implementations, you might tie up your entire codebase in a stringy mess. Engines encourage separation of concerns. Sure, you could just shove your entire game logic in one god object, but the engine gives you tools to express your problem as separate, smaller problems that loosely communicate with each other, so why not use them? In a framework, it's entirely up to you to keep your codebase tidy, as the framework is only concerned with shoveling the user input into your app and doing something with its output.

Model-View-Controller

As Robert Nystrom puts it, "You can’t throw a rock at a computer without hitting an application built using the Model-View-Controller architecture." This is a software design pattern worth everyone's salt, so go click the pothole right now if you know what's good for you.

In my game, I have a model Game struct that stores all the relevant state and has methods and stores scripts that define the logic to interact with the state. The game state only changes in response to specific user interactions, i.e. the user clicked to advance, or they chose a path at a junction. The problem is if we just use this to draw the game, we'd have things happen instantly, with no user feedback. This is Not Great™.

So, I want to add some tweening and whatnot to make the game flow visually in a pleasing manner. A first thought would be to shovel this additional state into the model, but these details are irrelevant for the actual game logic (and for reasons I cannot go into detail lest I derail the topic completely, the networking would be very unhappy. Floating point and networking don't mix).

Instead, I create a new GameView struct responsible for the tweening, the positioning, all that fun stuff. It updates its state whenever there are changes to the model, tracked sequentially with events, and also has the option to "fast-forward" the game state as if the view had just copied all the details from the model. This is Very Bangin™.

The whole gang is almost here. Where's the controller? Well, the controller, the thing that glues the model and view together, is a hotly debated part of the design pattern, to such a point where an alternative Model-View-Whatever is offered for use in discussions. In my app, the main application loop is the thing gluing the model and view together. That's the half (and other half) of it.

Why is this relevant if I work in an engine?

The design patterns I was forced to learn and use in my adventures with notan very much have applications within an engine. In a talk given to my game dev circle, I praised Entity Component System but was careful to conclude the talk with a cautionary "ECS is not a silver bullet." That's because there is not one thing that will solve every problem you encounter when programming a game!

Sometimes, to get a good, solid solution to a problem, you will have to take the escape hatches that engines offer you. Maybe you want your entire game model to be exposed to a scripting environment, but your engine doesn't like mass-borrows of game data, so you might be forced to contain your app logic in a smaller model with all the details abstracted away.

Okay, the above point might be a result of the horrifying Rust borrow checker and is not an issue that most game engines have. I'm sure there are a lot of other logistical problems with scripting environments.

Or maybe you want relevant parts of your game to act in a very deterministic way for easy networking, since determinism means all you need to sync is player input, like that in a fighting game. Extracting the relevant parts of your game to a system or server and just giving that a place in your engine's processing loop might be enough to quell anxiety and fear over your deterministic system.

Taking the time to explore these design practices was well worth it, even if I stay in the bumbling idiots with too much time on their hands category at the end of the day. If you're similarly satisfied with the pursuit of knowledge alone, I recommend the following further reading:

These can really help get you started on game projects quicker and easier, even if you find yourself within the luxury of a game engine.

For readers actually interested in the specific implementations of the code for my game, I will follow with an update later providing some links to some Git sources. It's open-source and dedicated to the public domain.

Send any notification of link rot to theguy@frostu8.rs.